Education

Students: Not Working is Not an Option

By Aniya Greene

Staff Writer

A student asked her for a roll of toilet paper.

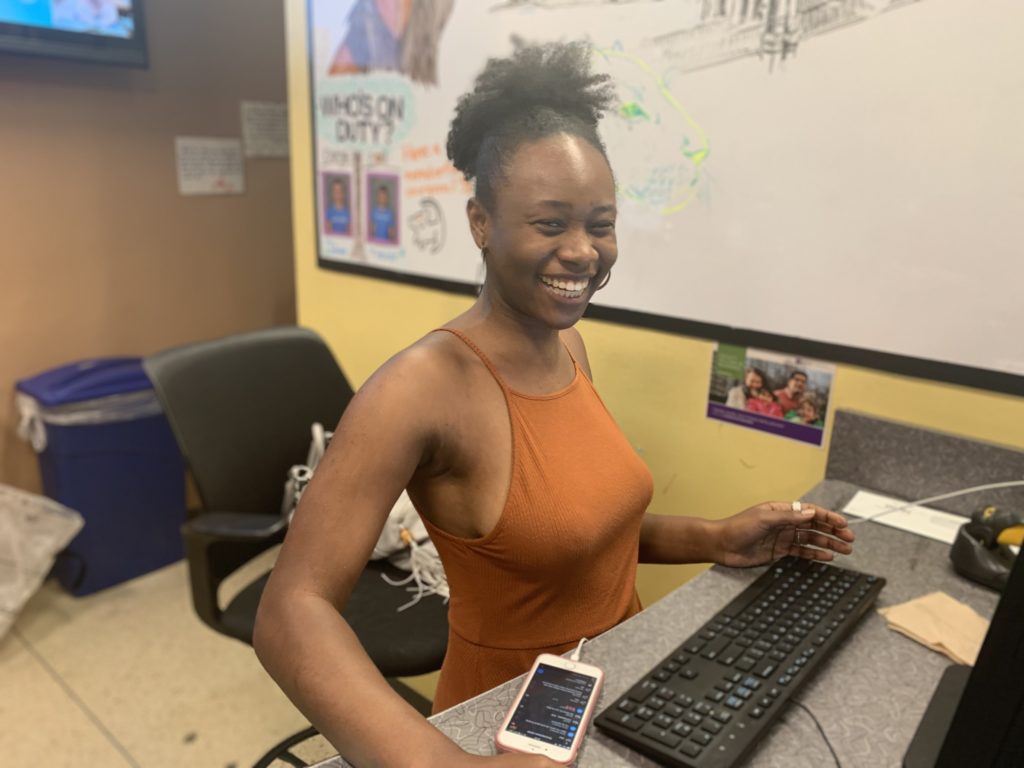

“Sure,” Ra Carroll answered, from where she sat behind the welcome desk at Palladium Hall dormitory.

For handing out toilet paper and door keys, pointing summer guests at that NYU dorm toward the best pizzeria and performing other duties, Carroll earns $15 an hour. She’s a work-study student, paid through a federal program that provides part-time employment for cash-strapped undergraduate and graduate students qualifying for financial aid.

She works, the sophomore biology major said, “to support [herself] and save up for any bills that may be due for a semester. Working, she added, “is how I eat.”

Carroll is not alone. With tuition historically high and still rising, more and more college students are working to help pay for the costs. Seventy-six percent of graduate students and 40 percent of undergraduates worked at least 30 hours per week, according to a 2015 report by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “Learning While Earning: The New Normal” also found that 25 percent of students worked full-time while they also were enrolled full-time in college.

In addition to working at a dormitory welcome desk, Carroll also helps conducts research on campus and does clerical and other tasks for NYU’s Office of University Events. Balancing that kind of schedule is tricky. “I don’t know how I manage. I feel like I’m always having a manic episode,” she said.

Carroll, though, counts herself lucky; she won enough scholarship dollars to avoid borrowing money to cover college costs. “If you’re smart enough or poor enough at NYU, they’ll give you enough money,” Carroll said.

The number of students graduating with college with loan debt rose to 69 percent in 2016 from 58 percent in 1996. They owed an average of $29,650 in 2016 and $12,750 in 1996, according to the Institute for College Access and Success.

Doraian Givens, a NYU junior majoring in marketing and producing black American music, is one of those students who’s had to take out loans. She also earns $50-a-head for braiding hair for her black women classmates. It is not regular income. Still, sometimes, she earns more each week braiding hair than in her work-study job at Weinstein Hall’s welcome desk.

In addition to taking out student loans, Ashley Quinonez, who begins her freshman year at NYU this fall, plans to work at Chipotle Mexican Grill during the academic year. “Living in the city is expensive, so I have to get a job. I don’t want to press my parents for money,” said Quinonez, who already works at Chipotle.

Quinonez’s financial aid package only covers half of her tuition. “I thought I was gonna get more [money],” she said.

She’s betting that attending such a competitive and respected school as NYU will be worth the high costs. “Everyone was telling me ‘Oh, it’s still a good school. After you graduate you can pay off your loans,’” said Quinonez, the first in her Bronx family to attend college.

About NYU’s $76,000-a-year pricetag, she added, “It’s a lot. I think they should cut down the costs.”

While she worries about how long she will need to work and if she can manage work and learning, she said, “My mom is always telling me you’re gonna be fine.”